I am an anxious person by nature. Crowds make me anxious. Driving at night makes me anxious. Loud noises in general, but shouting in particular, make me anxious — even if the shouting is not directed at me. But why? What makes me react to crowds this way, while others are not bothered in the least by crowds or loud noises?

There are probably lots of reasons. And, as with anything as complicated as the human brain, most of the reasons are probably intertwined with each other.

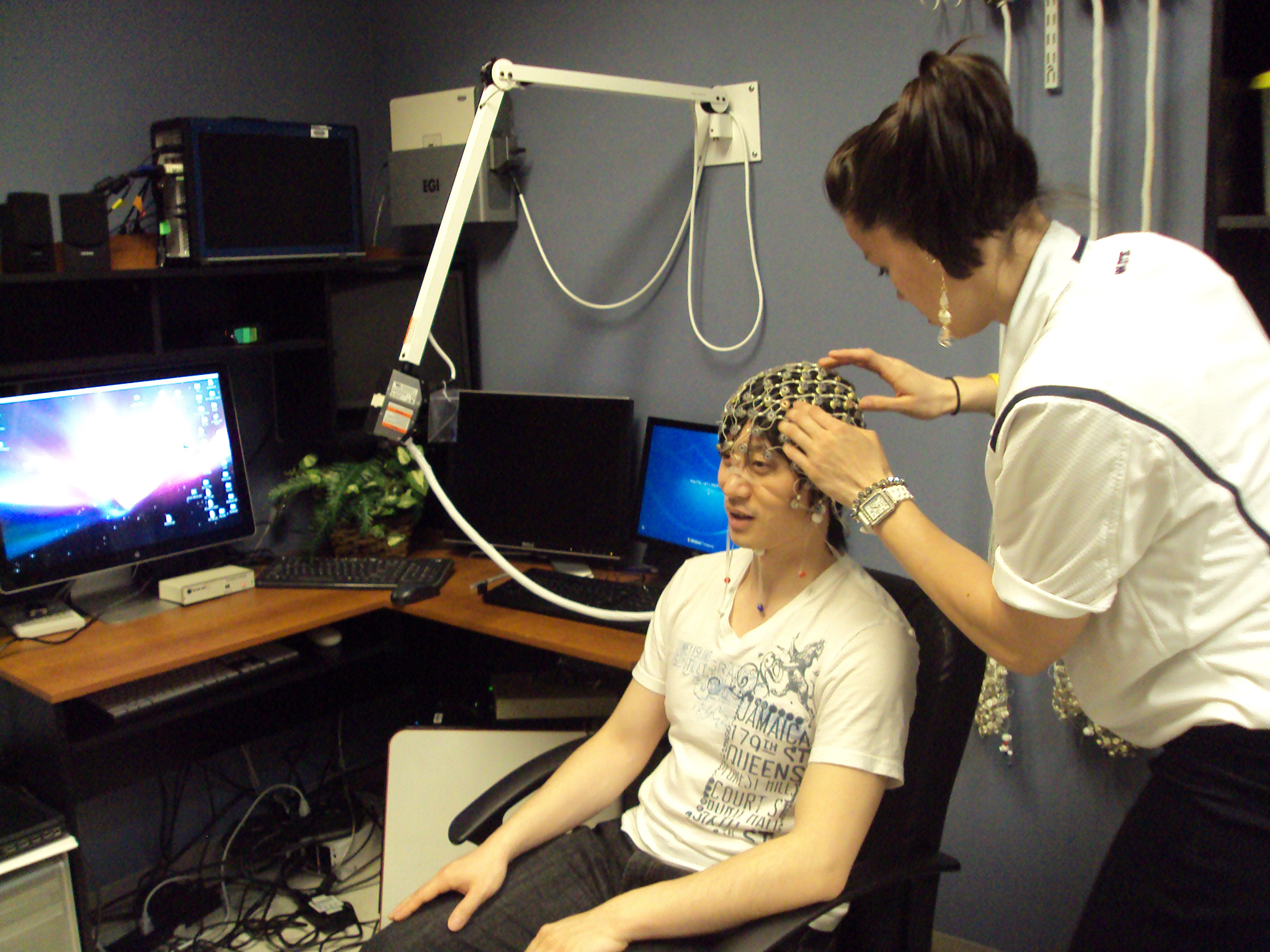

My therapist tells me anxiety is seeded in fear. I was recently talking with Koraly Pérez-Edgar, an associate professor of psychology here at Penn State, for last week’s episode of the Chemical Heritage Foundation’s Distillations podcast. She told me that shy people often have an overactive amygdala, but you can listen to our conversation here as part of a segment titled “Inside the brain.”

Fear, shyness, overactive amygdala. Hmm.

Pérez-Edgar explained that the limbic system is what shapes your response to threat and novelty in the environment. And at the center of the limbic system is the amygdala. The amygdala is known to be the seat of emotion and your fight-or-flight reaction. When stimulated, it triggers your nervous system to momentarily freeze, assess the situation (likely quicker than you have time to process it), and then either stay put and defend or run away — the basic survival instinct.

So somehow, my amygdala has decided that nighttime driving and shouting are reasons for me to run away. While I am not a shy person, as the people Pérez-Edgar studies are, many of the things she described match my gut reactions. Perhaps I have an overactive amygdala after all.

I also discovered during our conversation that the children’s toy the jack-in-the-box can be a terrifying experience for many babies who turn out to be shy and have an overly sensitive amygdala.

“A lot of babies, they giggle, they laugh, they think it’s funny,” Pérez-Edgar said of the jack-in-the-box. “But these [shy] babies are terrified. They’re crying, they arch their back, they move their arms back around, their system has just said DANGER.”

As she described these reactions to me, I thought about a jack-in-the-box and how unappealing that experience seems to me, as an adult.

Immediately after we were done talking, I texted my mom, wanting to know if I hated jack-in-the-boxes when I was a baby. She didn’t remember. How can you not remember your first-born’s every experience?? My boyfriend pointed out that the jack-in-the-box was not really a popular toy when we were growing up. He insists on being the reality check in my life.

In any case, a baby’s overactive amygdala is likely linked to either his genes or his environment — in utero, during early development, or both. Or both his genes and environment influenced the amygdala.

Do I have an overactive amygdala? And if I do, why? It’s probably not worth my time to figure out right now. Meanwhile, I’ll keep practicing yoga to help keep my anxiety in check.