I’m pretty sure I’ll never write my autobiography and I’m almost just as sure no one will write my biography unless I’m missing something. I’ve written thousands of stories in 38 years as a science writer so I’ll remain on the web forever. Doesn’t bother me.

Some people, without autobiographies or biographies, still end up memorialized in books, which is what recently happened to some Penn State faculty members from the College of Earth and Mineral Sciences.

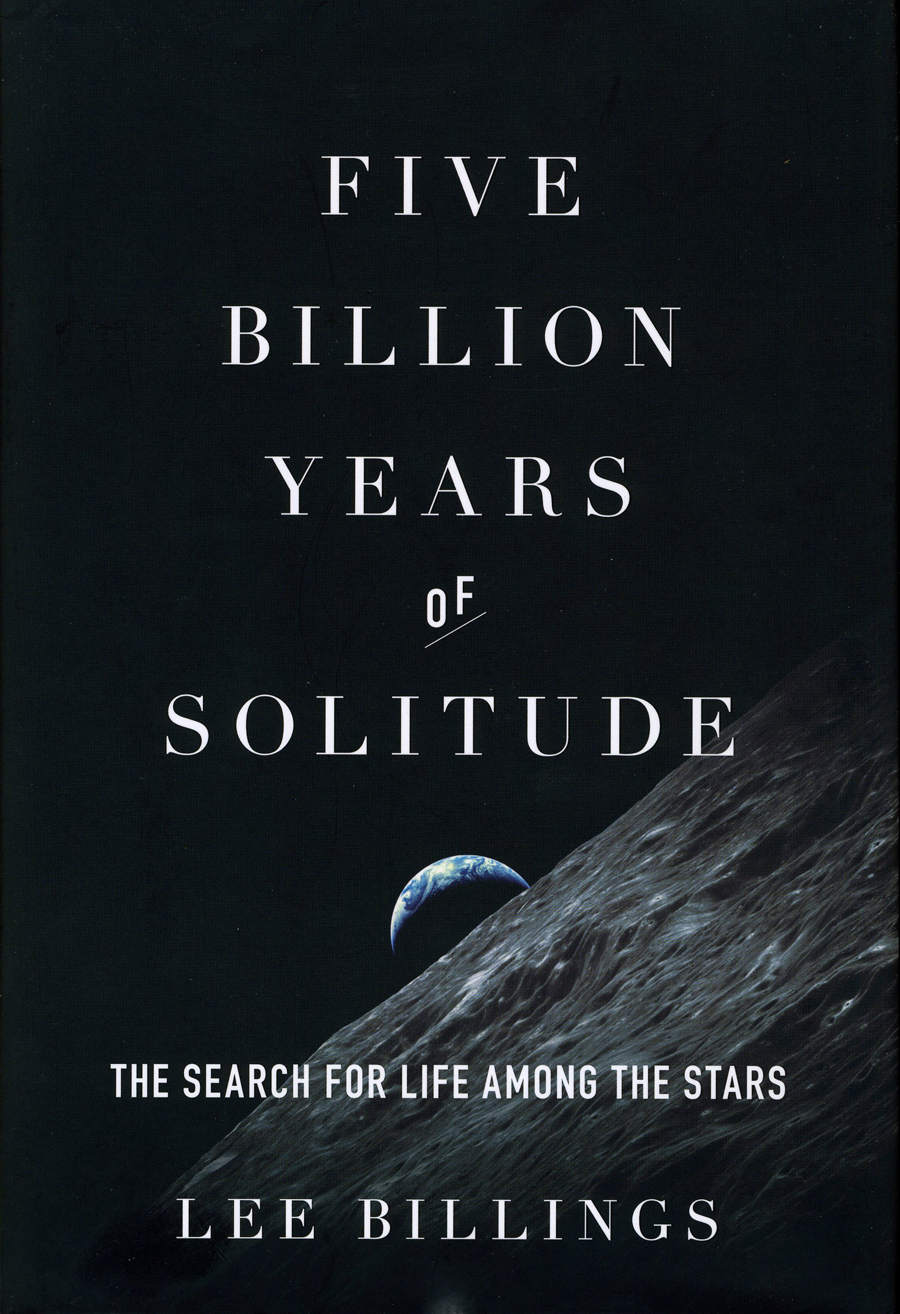

Another science writer, Lee Billings, wrote a book, “Five Billion Years of Solitude: The Search for Life Among the Stars,” which is about looking for other living, sentient beings in the universe. This book ended up on my desk because I get sent this type of book from time to time. I thought wow, I wonder if Jim Kasting, Evan Pugh Professor of Geosciences, was in the book. Looked in the index and sure enough he was, as was his twin brother, wife and children.

Not only was he in the book, but nearly an entire chapter, “Out of Equilibrium” was about his work, very cool.

But I was actually sent the book because another faculty member, Michael Arthur, professor of geosciences, former department head and co-director of  the Marcellus Center for Outreach and Research, was in the book. That’s what the letter that came with the book said. His chapter is “The Big Picture.” I was puzzled. Arthur is a sedimentary geologist. He studies how rocks are formed, so I wasn’t quite sure how he fit into this book. And the chapter talks about black shale, the Marcellus shale gas producing area and other petroleum and natural gas stuff. In fact, another Penn State faculty member mentioned is Terry Engelder, professor of geoscience, who initially estimated how much gas was in the Marcellus. I know, because I wrote that story. But then I read on and realized that Arthur was using the Marcellus shale, the last shale oil/gas deposit to show no terrestrial plant inclusions — it was formed before life moved to land — as an example of the evolution of intelligent life. And so the story moved from sea to land to animals of all kinds and finally to humans. Intelligent life one presumes. Although Lee refers to it as the sixth major extinction event, suggesting that humans in their agrarian onslaught homogenized the planet and wiped out myriad species. So the history of the Earth leads to the search for intelligent life in the universe.

the Marcellus Center for Outreach and Research, was in the book. That’s what the letter that came with the book said. His chapter is “The Big Picture.” I was puzzled. Arthur is a sedimentary geologist. He studies how rocks are formed, so I wasn’t quite sure how he fit into this book. And the chapter talks about black shale, the Marcellus shale gas producing area and other petroleum and natural gas stuff. In fact, another Penn State faculty member mentioned is Terry Engelder, professor of geoscience, who initially estimated how much gas was in the Marcellus. I know, because I wrote that story. But then I read on and realized that Arthur was using the Marcellus shale, the last shale oil/gas deposit to show no terrestrial plant inclusions — it was formed before life moved to land — as an example of the evolution of intelligent life. And so the story moved from sea to land to animals of all kinds and finally to humans. Intelligent life one presumes. Although Lee refers to it as the sixth major extinction event, suggesting that humans in their agrarian onslaught homogenized the planet and wiped out myriad species. So the history of the Earth leads to the search for intelligent life in the universe.

Kasting is known for his work on figuring out where, in the orbits around suns, habitable planets can exist. These planets must be at a distance from their suns so that throughout the time it takes for life to evolve to intelligent beings, water remains liquid — at least most of the time. So no totally frozen planets and no planets too hot for liquid water. This becomes complicated because suns change their power through times. Kasting also does work on the “faint young sun” paradox, which explains that the sun was weaker when young and grew stronger. This moves the habitable zone further out as a sun ages.

So Kasting and Arthur are memorialized in this book. One, for looking far into the universe and future, and one for looking far into the past and beneath the earth. Both trying to understand how we got where we are and how some other intelligent being might get there too.