On a good day in the science writing business it’s not so much the breakthroughs that impress us. It’s the process, and the people.

On a good day in the science writing business it’s not so much the breakthroughs that impress us. It’s the process, and the people.

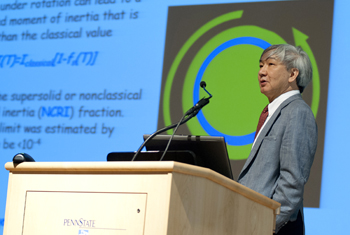

Back in 2004, when Penn State’s Moses Chan and his graduate student Eun-Seong Kim reported the “probable observation of a supersolid helium phase” in a letter to Nature, they made headlines around the world. It was, as Science News noted this week, “one of the most exciting physics discoveries in recent years.”

What Chan and Kim had apparently discovered, after all, was nothing less than a brand new state of matter, “a mysterious substance that could float through ordinary solids like a ghost through walls,” according to physicsworld.com. Science News’ Alexandra Witze calls it “the stuff Nobel prizes are made of.”

In the eight years since, Chan, one of the University’s most distinguished (and most personable) researchers, has been attempting to repeat that amazing result. So have his colleagues in other condensed-matter labs around the world: trying either to uphold Chan’s finding or to knock it flat: this, after all, is the sober majesty of science.

Over the years, Witzke reports, there have been some experiments that seemed to confirm Chan’s observation, and others that did not, but none that has been found to be conclusive. John Beamish, a physicist at the University of Alberta in Canada, whose own work cast doubts on Chan’s result, notes, “It was continually surprising to those of us working in the field just how hard it was to confirm or disprove the existence of supersolidity.”

Chan himself went back to the drawing board relentlessly, rebuilding his experimental apparatus again and again, trying to eliminate any possibility of distorting effects. Repeating the initial experiment.

Last week, in a paper published in Physical Review Letters, he announced his new findings. They do not confirm his earlier conclusion, but reverse it. It was not the behavior of a supersolid that he and Kim observed in 2004, Chan now contends, but the ordinary stiffening of helium at extremely low temperatures.

I find Chan’s accompanying comments, reported in physicsworld.com, to be quietly compelling. He expresses, understandably, a sense of disappointment. It was “embarrassing, in a way,” he says, that the reinterpretation had taken so long. “It would have been nice,” he adds simply, [if supersolidity had held up], “but Mother Nature had her own way.”

Maybe all this is just par for the course. Maybe it is (or ought to be) less than remarkable. Moses Chan surely doesn’t need me to commend him, at any rate. But if we science writers are—and well we should be—ever quick to sound the claxons when a researcher cheats or cuts corners, I think it’s also worth noting when one of them so clearly models diligence and integrity.

Chan’s colleagues apparently agree. In the physicsworld.com article, Beamish praises him for pursuing the science “with amazing energy, even when his new experiments disagreed with his interpretation of his initial experiments.” An accompanying photo of Chan, lecturing recently in University Park, includes a fitting caption. It reads:

“Moses Chan shows how science should be done.”