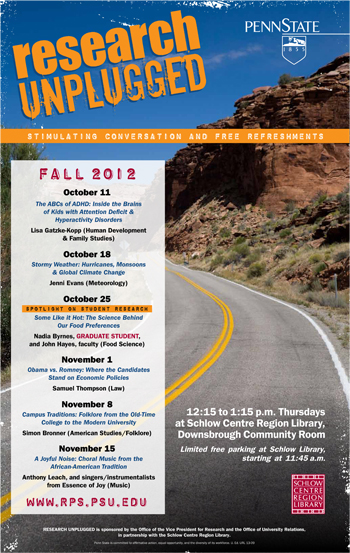

We’re feeling a bit like proud parents around here lately. Research Unplugged—the Penn State speaker series that took its original inspiration from Europe’s vibrant Cafe Scientifique scene—turned nine years old this fall! With last season’s decision to partner with (and hold events at) Schlow Center Region Library, a weekly turnout of 75 to 100 area residents of all ages, and vibrant Q&A sessions on topics across the disciplines, Unplugged is not only surviving but thriving!

Penn State in Chicago!

I just blew in from the Windy City where we had a very successful Research on the Road event with the good folks from the Greater Chicago Chapter of our Alumni Association.

Research on the Road is the University’s new speaker series that brings Penn State faculty to alumni chapters around the country for lively conversations on a wide assortment of research topics. And lively it was! We were so fortunate to have Jerry Zolten, “roots music” historian and associate professor of communication arts and sciences, as our speaker, and to have more than fifty enthusiastic Penn State alumni and friends in attendance at one of Chicago’s most famous blues clubs, Buddy Guy’s Legends.

Happy anniversary Ag College of Pennsylvania!

A colleague reminded me the other day that 2012 is a milestone year in Penn State’s history: 150 years ago, the Farmers’ High School—the name under which the University was incorporated in 1855—became the Agricultural College of Pennsylvania.

Two more name changes lay in the future. The ACP became the Pennsylvania State College in 1874, which in turn became The Pennsylvania State University in 1953.

So what’s the big deal about the Agricultural College of Pennsylvania? And what does it have to do with research? (This is a research blog, after all.)

Take a look at the ACP’s seal – jam-packed with two dozen or so objects that suggest many areas of higher learning, including a test tube and a microscope and probably a few other items (that I can’t identify) used at that time in scientific research. (See all of Penn State’s official seals here.)

The ACP seal would be a nightmare in today’s world of sophisticated “branding.” But in 1862, its graphic elements reflected the blend of teaching and research activities that founding President Evan Pugh envisioned for Penn State. Pugh himself was a brilliant chemist who won international recognition for his experiments on the use of nitrogen by plants.

The name and seal of the Agricultural College of Pennsylvania were intended to strengthen the institution’s case to become Pennsylvania’s land-grant endowment. By early 1862, the High School’s Board of Trustees recognized that Congress would soon enact legislation establishing a nationwide system of land-grant colleges. Representative Justin Morrill’s bill called for each state legislature to designate one or more institutions as land-grant colleges. In exchange for offering instruction in scientific agriculture and in engineering, these colleges would receive an endowment created by sales of federal land. (Go here for more particulars.)

The Farmers’ High School had been established as a college of scientific agriculture, and in fact awarded the nation’s first baccalaureate degrees in that subject in 1861. Its founders had chosen the name “high school” for fear that farmers would be prejudiced against enrolling their sons in a “college,” which were widely perceived as places where boys typically partook of drinking and card playing, and otherwise developed evil habits.

But with the passage of the Morrill Land-Grant Act, the Trustees reversed their thinking. The “High School” moniker could weaken their claim that their institution was of baccalaureate-level quality. Numerous other colleges laid claim to Pennsylvania’s land-grant endowment; the competition was fierce. Supporters of the new ACP had to use every weapon in their arsenal.

They succeeded. On April 1, 1863, Pennsylvania designated what we know as Penn State as the Commonwealth’s sole land-grant college, and it has been thus ever since. The land-grant designation bestowed on Penn State its historic mission of teaching, research, and public service.

Also in 1863, the Agricultural College of Pennsylvania awarded its first graduate degrees—two masters of scientific agriculture. But that’s another story—and another anniversary. Watch for more about the 150th anniversary of graduate education at Penn State during the 2012-13 academic year.

Under the Sea: Mermaid Excluded

The city of Akko is on a peninsula surrounded by water. Situated at the northern most point of greater Haifa Harbor, the Mediterranean surrounds the Old and New cities.

Maritime endeavors have always been important to the inhabitants of Akko, which was a Phoenician city during the Iron Age, and we all learned in grade school, or should have, that the Phoenicians were the sailors and traders of the Mediterranean Sea.

Interestingly, I’m surrounded by archaeologists who are totally interested in the Iron Age and they all agree, very little is actually known about the Phoenicians. Looking at the Phoenicians is one of the objectives of the Total Archaeology @ Tel Akko project and while digging on the tel can tell us how they lived on land, exploring under the harbor might provide a clue as to how they lived on water.

Akko harbor is certainly known from Crusader history and during the Hellenistic period, the city was renamed Ptolomais and the harbor was very important. Alexander the Great entered through Ptolomais on his way further east.

Hence the mermaid reference. Supposedly, there is a female mermaid-like entity that appears near the Tower of Flies and asks, “Has he returned yet.” She is supposedly asking after Alexander.

And the Tower of Flies, that too has a story. When the Crusaders came to Akko or St. Jean d’ Acre, they thought they had reached Ekron, where one of the major deities was Ba’al Zevuv – Lord of the Flies (I kid you not). Since the tower already existed and apparently garbage was dumped there frequently, the Crusaders named it the Tower of Flies.

But to the harbor. Centuries of sediment deposition from the small river that flows into the Mediterranean near Akko and natural ocean processes have undoubtedly changed the shoreline, covered evidence and filled in any number of harbor manifestations. The only way to find the Phoenician harbor is to dig — underwater.

Total Archaeology@Tel Akko includes an underwater archaeology component and while they haven’t yet found the Phoenician harbor, they are bringing up some interesting results.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MY6nFS9ncHs]

Not Panning for Gold

Credit: Jill Bierly

I was wet screening some dirt from the probable metals working area the other day, sitting under a shade near the path that winds up and around Napoleon Hill (Tel Akko) when two small boys, 8 or 9 I’d guess, walked by. They asked me in Hebrew if I was looking for gold. I said no, iron. They gave me the strangest look, stopped for a second, and then began walking on. As they got about 6 feet in front of me they turned and said, you are looking for gold. And they walked off.

Gold and silver, those are the precious metals that everyone thinks of when they think of prospecting or looking for ores and such. But, for archaeologists in most places, the use of copper and then iron ores for metalworking is far more important. Copper is the only metal beside gold and silver that occurs in its native form on Earth. Just as one can find gold nuggets, copper nuggets – not as shiny bright and not as valuable – are also found. Native copper is the only indication of metal working of any kind in North America in pre-contact times. The nuggets were hammered into tiny bells or other ornaments, but Native Americans never smelted copper or any other metal.

In the Middle East, however, copper, bronze and eventually iron were smelted and worked. Last year at Tel Akko, during the excavation by the Penn State and University of Haifa, Tel Akko project, excavations revealed a potential metal working area. This year, a new area, next to the original was excavated and examined by students and a researcher from the Weizmann Institute.

Remember Wooly Willie or other metal filings games where you move the iron with a magnet to create hair, beards, etc.? Run a magnet through the dirt in these two areas and the magnet looks like Wooly Willie with a full beard. The number of hammerscales – tiny pieces of iron that fall off when hammering iron into shape – is truly amazing. The area also yielded pounds of iron slag. In other areas of the Tel copper slag appeared as well.

The first or second day of the dig, I found, in situ – in the ground in the original location – part of an iron blade. Yes, I was digging in the same location with all the hammerscales. Today, one of the last days of digging, someone found an iron arrowhead that is probably late Iron Age early Persian.

Some say that Akko was famous for metalworking. Certainly indications from this year’s excavations suggest that some ironworking went on in the Persian period, if not earlier.

[youtube http://youtu.be/XcT_oMyp8PA]